The Sweet Spot of Intensity

The pandemic’s effect on access to facilities has forced us to look for other ways to continue building toward our fitness goals. While some of us have a big enough exercise library in our brain to build a program with, perhaps the most challenging part of this process is finding ways to structure your at-home workouts when weight is limited or, in some cases, unavailable. If you’re anything like me, I typically try to identify key components in a regular scenario and draw parallels to the new situation in the hopes that I can find old solutions to new problems. So what factors are at play under regular circumstances and how can we adjust them to fit our current training environment?

enough exercise library in our brain to build a program with, perhaps the most challenging part of this process is finding ways to structure your at-home workouts when weight is limited or, in some cases, unavailable. If you’re anything like me, I typically try to identify key components in a regular scenario and draw parallels to the new situation in the hopes that I can find old solutions to new problems. So what factors are at play under regular circumstances and how can we adjust them to fit our current training environment?

In resistance training and exercise, the main way we measure training stress is called Volume Load. VL is quite simply a measure of the amount of work prescribed and is the sum of the following factors:

- Number of sets and repetitions (Volume).

- The proximity to failure, typically a percentage of your overall capacity, that the weight lifted, or repetitions performed, take you to.

(Intensity).

Most commonly, we increase training stress by looking at the amount of weight lifted for a given number of repetitions for an exercise. If we want to increase VL, we increase the weight for the same number of sets and/or repetitions. This is a pragmatic approach as it isolates a single variable (weight-lifted) to progress the training stimulus. However, a condition of taking this approach to planning and monitoring progress is that it potentially requires a lot of equipment and weight – something we mentioned earlier. So, what components of Volume Load can we adjust to change how stressful our training is?

At home, the weight likely is the same, which means to allow for certain proximity to failure to stimulate progress, we need to be able to adjust the sets and or repetitions. When we compare these two variables, however, a consensus is that adjusting repetitions is the most sustainable over the long-term because the increases in VL are easier to adapt to, relatively speaking, than increases in sets (Deweese, Hornsby, Stone, & Stone, 2015). For example, if we start week one with three sets and add a single set each week, after six weeks we would be performing nine sets per exercise – that’s a 300% increase in Volume Load.

| Week | Increase in Sets | Increase in Repetitions | ||||

| Sets | Repetitions | Weekly VL | Sets | Repetitions | Weekly VL | |

| 1 | 3 | 10 | 30 | 3 | 10 | 30 |

| 2 | 4 | 10 | 40 | 3 | 11 | 33 |

| 3 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 3 | 12 | 36 |

| 4 | 6 | 10 | 60 | 3 | 13 | 39 |

| 5 | 7 | 10 | 70 | 3 | 14 | 42 |

| 6 | 8 | 10 | 80 | 3 | 15 | 45 |

| 7 | 9 | 10 | 90 | 3 | 16 | 48 |

| Total VL | 420 | Total VL | 273 | |||

Assuming that in week one, both examples were above a minimum threshold of intensity and volume to be beneficial, one might suggest that the increase in sets may cause detrimental effects over the long-term as the increase in stress may exceed the body’s ability to adapt.

From a long-term perspective, it appears that adjusting repetitions, when the load is unavailable, is the more practical approach. Conveniently, there is a method we can use which is adopted from Strength and Power training that can be utilized to adjust for proximity to failure.

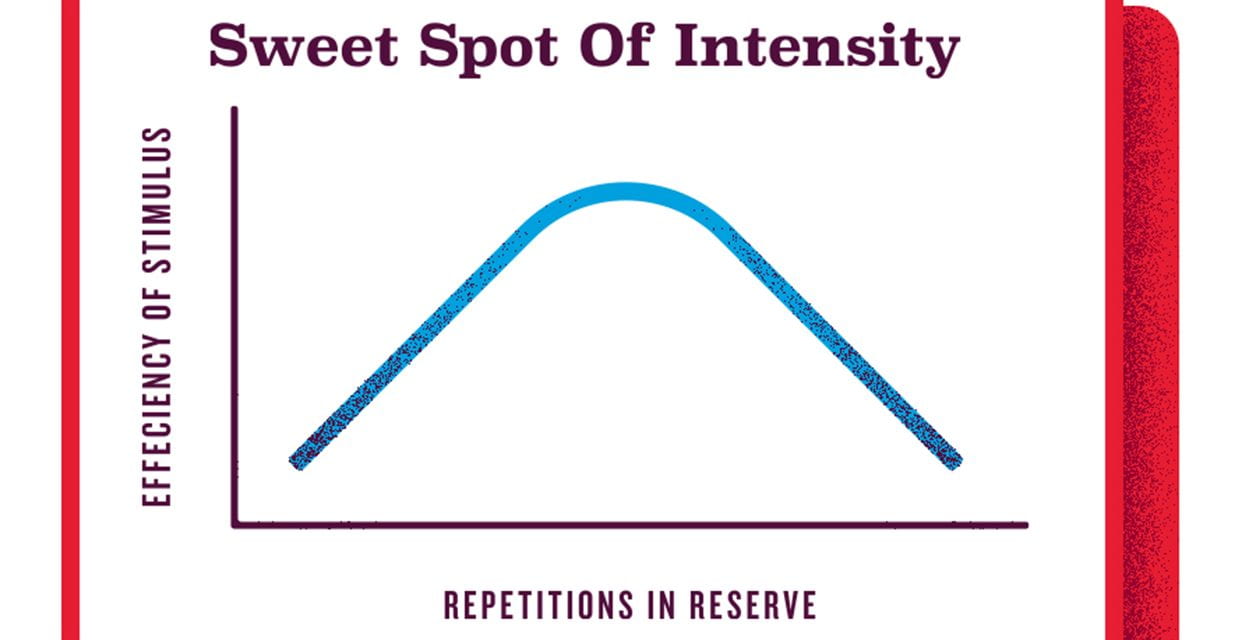

This method for intensity prescription is called Repetitions in Reserve (R.I.R. for short) and it represents your proximity to failure in a set under a given load (Deweese, Sams, & Serano, Sliding Toward Sochi – Part 1: A review of Programming tactics used during the 2010-2014 Quadrennial, 2014). While this method has not been validated for the high repetition (>10 repetitions) zones that one might encounter in a bodyweight-only environment, it does provide a logical way to progress intensity over time, which is a necessity to continue seeing results (Deweese, Hornsby, Stone, & Stone, 2015). This method is held up by the fact that volitional failure is not required to stimulate adaptations in the muscle (Carroll, et al., 2019). This means that as long as we are hitting a minimum threshold of intensity and volume, failure is not required for things like caloric expenditure, muscle growth, strength and power improvements (Carroll, et al., 2019).

In practice, this looks like choosing an exercise and a desired number of sets and, determine the proximity to failure that you will work up to.

For example, If I were to perform a set of pushups to an R.I.R of “five” I will perform pushups until I reach a number of repetitions where I feel that I can only perform five additional pushups. At that point, I will end my set. Each set I will perform the same process – perform repetitions of the exercise until I reach my pre-determined R.I.R. Typically, once you record your number of repetitions completed in your first set, you would perform the same number of repetitions in the following sets (Deweese, Sams, & Serano, 2014). It is important to note that, because R.I.R is essentially a measure of perceived fatigue, less rest between sets will presumably cause us to reach our R.I.R at a lower number of reps which may have mixed results based on our overall objective of training (Robinson, et al., 1995) (Stone & O’Bryant, 1987).

Over longer time-periods (weeks, months, etc.), reducing the R.I.R from week to week allows us to get closer to failure and therefore make the exercise more intense, increasing overall training stimulus.

| Week | Traditional Progression | RIR |

| 1 | 3×10 @ 60% of 1 Rep Max | 6-7 |

| 2 | 3×10 @ 65% of 1 Rep Max | 5-6 |

| 3 | 3×10 @ 70% of 1 Rep Max | 2-3 |

| 4 | 3×10 @ 60% of 1 Rep Max | 6-7 |

This approach allows us to give our best effort while also recognizing that our “best” will change every day due to a convergence of many things beyond our control (stress, diet, etc.).

Like most instances this year, it is not necessarily about what is ideal but what is possible in the current situation we find ourselves in. Systems like Repetitions in Reserve allow us to pivot to a new strategy for planning our fitness.

by Devin Clayton

Devin is a Bachelor of Physical Education graduate from the University of Alberta. He is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA and is an NCCP certified Weightlifting coach.

Carroll, K. M., Bazyler, C. D., Bernards, J. R., Taber, C. B., Stuart, C. A., Deweese, B. H., . . . Stone, M. H. (2019). Skeletal Muscle Fibre Adaptations Following Resistance Training Using Repetitions Maximum or Relative Intensity. Sports.

Deweese, B., Hornsby, G., Stone, M., & Stone, M. H. (2015). The Training Process: Planning for Strength-Power Training in Track and Field Part 2: Practical and Applied Aspects. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 318-324.

Deweese, B., Sams, M., & Serano, A. (2014, August). Sliding Toward Sochi – Part 1: A review of Programming tactics used during the 2010-2014 Quadrennial. NSCA Coach, pp. 30-43.

Robinson, J. M., Stone, M. H., Johnson, R. L., Penland, C. M., Warren, B. J., & Lewis, R. D. (1995). Effects of Different Weight Training Exercise/Rest Intervals on Strength, Power, and High-Intensity Exercise Endurance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 216-221.

Stone, M., & O’Bryant, H. (1987). Weight Training – A Scientific Approach. Edina: Bellwether Press.