When returning to a fitness routine, it is wise to acknowledge or assume that there has been some sort of regression in your fitness since you last were on consistent practice. While routines differ in timelines, overall objectives, most resistance training routines follow a general structure such as this:

Essentially, you begin with routines that are more “stressful” on your system and gradually reduce the stress by decreasing the amount of work you do while increasing the resistance you do it with.

A typical example of this in practice is going from higher repetitions to lower repetitions while increasing the weights.

Many of us will face a regression after an extended break from exercise due to a decrease in our level of fitness, the routine that we used to do may now be more stressful or too stressful for us to complete with the same results that we had in the past. This can be potentially problematic if we don’t make proper adjustments to ensure what we are asking ourselves to do doesn’t exceed what we can recover from. Adverse outcomes associated with excess training-related stress can range from extremes of hormonal dis-regulation and heightened injury risk to things seemingly as trivial as negative mood states and missed training times (Foster, 1998). One of the most critical factors in training is consistency, failures in planning our training can cause us to fall short of our fitness goals (Cleather, 2018).

So the trick becomes finding an amount of work and time, initially, that allows us to:

- Assess our level of fitness to inform future training stressors.

- Keep training stress low-moderate to mitigate potential adverse outcomes of doing “too much too soon.”

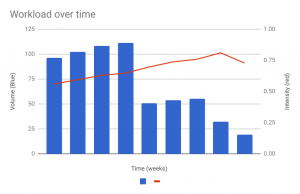

A simple way of achieving these objectives is choosing a similar structure to what you were doing prior to your training but adjusting the workload. Changing factors such as weight/resistance, duration, sets and/or repetitions, or training sessions/week to a lower level than previously completed. Progressing these metrics over one to three weeks will allow you to build your physical abilities into a position where you can more accurately test and assess your fitness level while ensuring you’re doing an amount of work that your body can recover from.

The best part of all is that you will now be able to prescribe periods of more aggressive training with a little more assurance that the workload will be within your current fitness level.

So start slow and progress one step at a time. Understand that being successful in your fitness endeavours requires a certain level of consistency. Consistent progression beats out erratic periods of highly stressful workouts – so plan accordingly.

Visit our website for information on training consultations, virtual coaching, and personal training. Sign-up to receive our monthly newsletter for news, announcements, program information, swim tips, and exercise demos.

by Devin Clayton

Devin is a Bachelor of Physical Education graduate from the University of Alberta. He is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist through the NSCA and is an NCCP certified Weightlifting coach.

References

Cleather, D. (2018). The little black book of training wisdom. Lexington.

Foster, C. (1998). Monitoring training in athletes with reference to the overtraining syndrome. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 1164-1168.